This is the second or third installment of “Resources for Resistance,” depending on whether you start counting from one, “Resources for Resistance,” or zero, “Choose Your Adventure,” which I did not know would be part of a series when I wrote it.

In “installment one,” “Resources for Resistance,” I included the plea of Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez (AOC) to “meet your neighbors,” and build community.

I think this is a capital idea, and my point here is not to criticize, but to add to it, to say “Yes, and….”

Alvin Goulder wrote about “the metaphysical pathos of bureaucracy.”1 Basically, he argued that bureaucracy gets a bad rap, as we might say more colloquially, as providing only red tape. He also talked about how the existence of rules meant that they could be appealed to, for example, in redress of grievances. At Rational Software, which was purchased by IBM, there was a saying “do your eight (hours) and out the gate.” Working more than a designated number of hours per week, 35 or 40, will trigger overtime pay. Requests for an employee to work longer than what’s required could be resisted with appeal to the rules.

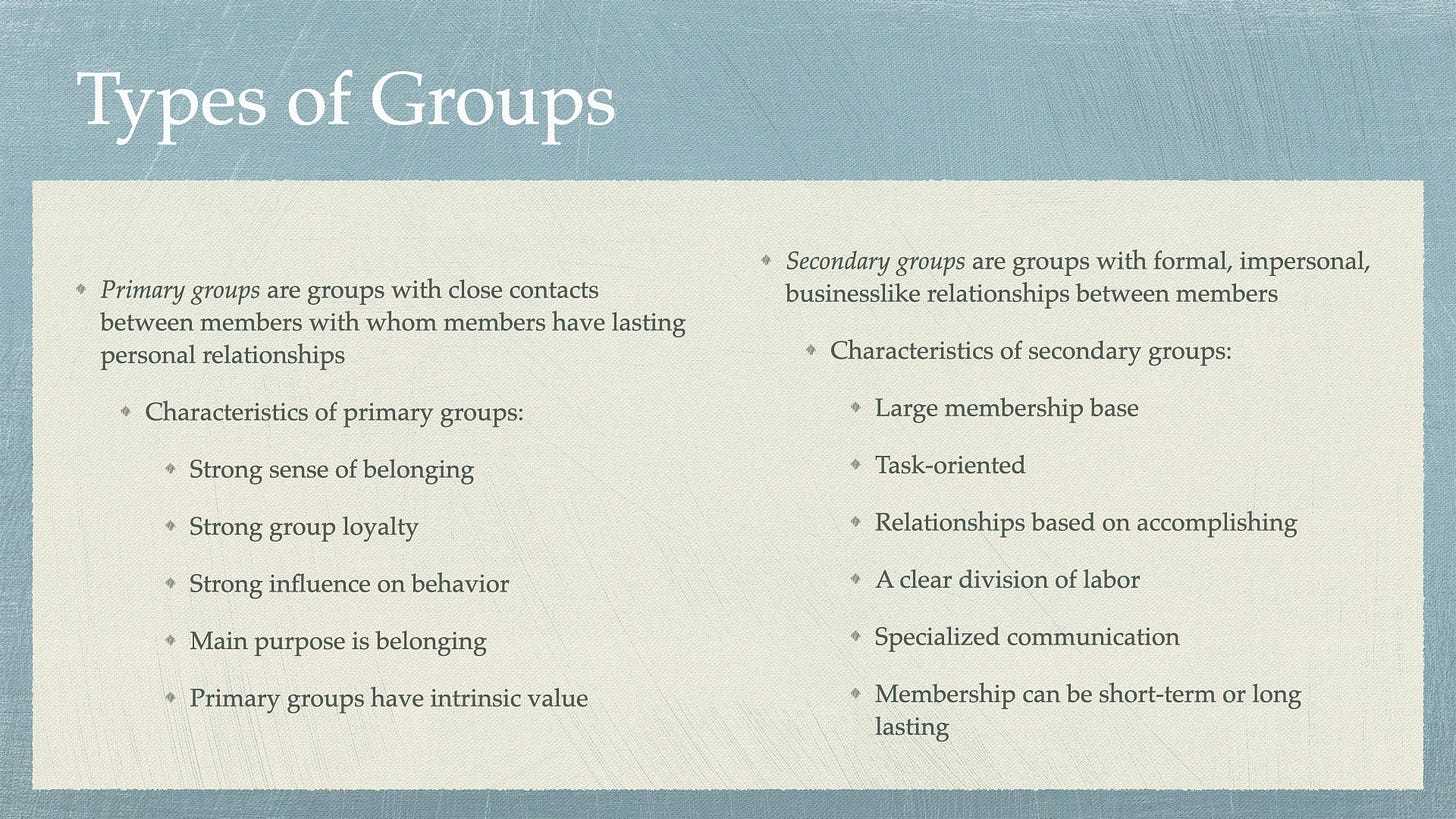

I think we might argue there also is a “metaphysical pathos” attached to close–knit groups. The sociologist Charles Horton Cooley introduced the idea of “primary” and “secondary groups.”

We value primary groups because they have intrinsic value, and I think we value secondary groups less because of the primacy of work in US society.

In the early days of the analysis of social networks—and by this I do not mean social media—Mark Granovetter argued that weak ties have strengths that strong ties, such as those we might experience in primary groups, do not. Sociologists propose that there is interaction between “levels” of social reality. Micro analyses focus on interaction in small groups, that could be face–to–face. Macro analyses focus on larger scale social structures. It is not enough to propose this interaction exists. It is important to document it through research. This is what Granovetter attempted to do. He argued that weak ties had the capacity to bridge close knit groups, and that this had implications for larger scale analyses.2

As an example of such implications, he drew upon the work of Herbert Gans on the unsuccessful efforts of residents of the West End of Boston to resist the urban renewal that would ultimately result in the erasure of that neighborhood.3 Granovetter speculated that

Unless each person was strongly tied to all others in the community, network structure did indeed break down into the isolated cliques… (1374)

Further, he argued

Weak ties are more likely to link members of different small groups than are strong ones, which tend to be concentrated within particular groups.

In other words, Granovetter argued that the absence of weak ties between close–knit groups may have been a factor in the inability to resist urban renewal.

Gans, who wrote the original analysis of the West End, did take issue with argument, back when letters could be submitted to a leading journal of sociology as “Commentary and Debate.”

;I think Granovetter also overestimates the importance of weak ties and the networks resulting from them, at least when he reanalyzes my data from Boston's West End (Gans 1962). In his reanalysis, Granovetter suggests that the West Enders were unable to fight the slum-clearance plan because their working-class ethnic social system emphasized cliques or peer groups, as I called them based on strong ties, and because weak ties between these cliques were lacking, leaving the neighborhood so fragmented that the cliques could not connect with each other to organize against the bulldozer.…

…I would argue that historical, cultural, and, above all, political factors explain the West Enders' failure to fight renewal better than do "weak-tie" and "network" factors.4

Not to be outdone, Granovetter counters with his own letter.

My main point is that these network structures and characteristics are important variables affecting the outcome of political and other processes, and are not either easily visible or deducible from general analysis of cultural, political, or economic variables. It follows that a part of any research on problems like the West End ought to consider networks directly.5

We can treat this debate as mere academic gamesmanship, or we can gain from it some real practical conclusions.

When I was first teaching, sociology, the TV series “The Ghost Whisperer” was one of my guilty pleasures. The premise was that Melinda Gordon, played by Jennifer Love Hewitt, could see and communicate with the dead, often reuniting them briefly with their loved ones and bringing them peace enough to “cross over.” For a while I maintained a Tumblog, “The Structure Whisperer,” for my students. The premise was that “I can see (social) structures,” inasmuch as Gordon would declare “I can see ghosts.” I think many sociologists are “structure whisperers,” in that they see what is invisible to many, the hidden connectedness between us. I think Granovetter is playing “structure whisperer” here.

What is the bottom line practical advice?

Don’t let the development of strong ties within the close–knit relationships you develop in resistance isolate and insulate you.

Close–knit relationships can nourish and protect us vitally. The Waging Nonviolence article to which I referred in Installment Zero, “Choose Your Adventure,” discusses the importance of “affinity groups.”

In extreme cases, like Chile in the 1970s and ‘80s, the dictatorship aimed to keep people in such tiny nodes of trust that everyone was an island unto themselves. At social gatherings and parties, people would commonly not introduce each other by name out of fear of being too involved. Fear breeds distance.

We have to consciously break that distance. In Chile they organized under the guise of affinity groups. This was, as its name suggests, people who shared some connections and trust. Finding just a few people who you trust to regularly act with and touch base with is central.

Find people you trust to meet with regularly. (What If Trump Wins/Elizabeth Beier)

Following Trump’s win: Get some people to regularly touch base with. Use that trust to explore your own thinking and support each other to stay sharp and grounded.

For the last several months I’ve been hosting a regular group at my house to “explore what is up with these times.” Our crew thinks differently but invests in trust. We emote, cry, sing, laugh, sit in stillness and think together. “10 ways to be prepared and grounded now that Trump has won”

But don’t let the affinity groups themselves be isolated. Allow your weak ties to other groups to create bridges between these affinity groups.

I think this is especially important as we consider the “marginalized,” “structurally powerless,” or most accurately, the “strategically undervalued.” Remember that US hyperindividualism treats disadvantage as a question of character, an inability to pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Consider it instead a structural accomplishment. Re–structure this through your weak ties. The multiplicity of our social roles can provide “weak ties” to bridge close–knit groups, creating greater strength of resistance overall.

In Installment One, I posted a link to an excerpt of the movie “Gandhi,” describing a “day of prayer and fasting (general strike).” Particularly telling is when Gandhi takes the tea tray from the servant of Ali Jinnah, who would later collaborate with the British during the Second World War, and work to establish Pakistan. Those of us with even a modicum of privilege should embrace the service of bridging.

Fully cognizant of “historical, cultural, and political” factors, then, develop affinity groups, and use the multiplicity of your social statuses to bridge your groups to others.

Gouldner, Alvin W. “Metaphysical Pathos and the Theory of Bureaucracy.” The American Political Science Review 49, no. 2 (1955): 496–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/1951818.

Granovetter, Mark S. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 6 (1973): 1360–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392.

Gans, Herbert. 1962. The Urban Villagers. New York: Free Press.

Gans, Herbert J. “Gans on Granovetter’s ‘Strength of Weak Ties.’” American Journal of Sociology 80, no. 2 (1974): 524–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777513.

Granovetter, Mark. “Granovetter Replies to Gans.” American Journal of Sociology 80, no. 2 (1974): 527–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777514.