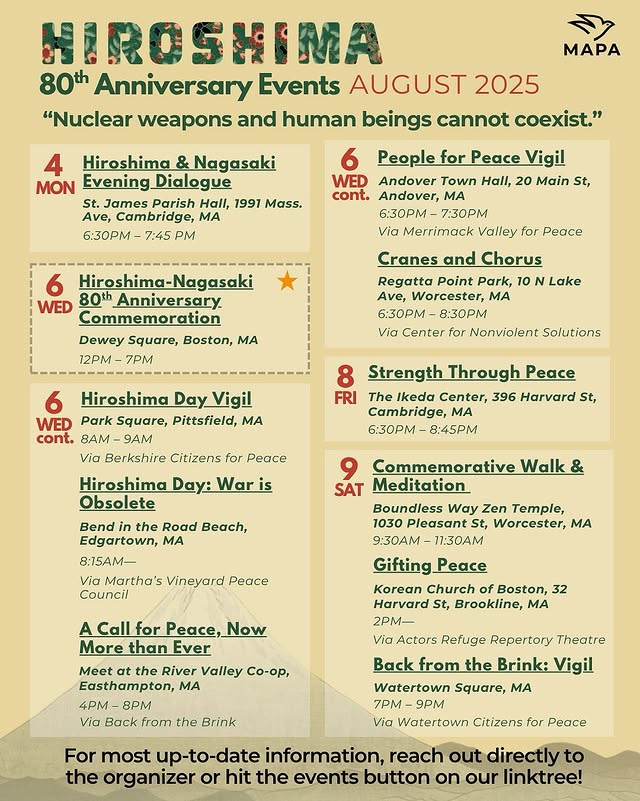

The Ninth Decade

Nuclear war, actual and threatened, enters its ninth decade today.

Cenotaph at Peace Park in Hiroshima Japan

Whenever I consider the sad anniversary of the first atomic bomb used in war, I consider the words of Mohandas K. Gandhi.

I did not move a muscle when I first heard that the atom bomb had wiped out Hiroshima. On the contrary, I said to myself ‘unless now the world adopts nonviolence, it will spell certain suicide for mankind’. (Mettacenter.org)

Jonathan Schell, author of The Fate of the Earth, penned during the era of the Nuclear Freeze Movement, also wrote an appraisal of US nuclear policy up through the administration of George W. Bush, entitled The Seventh Decade.

I assigned this book, part of The American Empire Project, to my classes in the Sociology of War and Peace, for a book review assignment. It was one among several I offered for them to choose. Its brevity was deceiving, because it was dense, if eminently readable. Among the amazing things I learned was that Pres. Ronald Reagan, of “Star Wars” (Strategic Defense Initiative) and “Evil Empire” (USSR) was at the end of the day, a nuclear abolitionist. Declassified documents obtained by Schell detailed the negotiations between Reagan and Gorbachev at Reykjavik.

“Well, Mikhail, we’ll come back in ten years, and we’ll each bring the last missile with us, and we’ll destroy them, and then we’ll throw a tremendous party for the whole world…” [Interview with Jonathan Schell, DemocracyNow!]

Indeed, Schell documents how staff like Schultz pulled Reagan back from what they viewed as the brink of abolitionism. How curious that years later, Schultz would advocate for this very position. But in The Seventh Decade, Schell documented George W. Bush would move us closer to a policy of “first use,” of a preemptive strike. The post–9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq showed us how conventional weapons like “bunker busters” could grow larger, even as nukes grew smaller, narrowing the firebreak of resort to nuclear war. Indeed, as late as yesterday, the Russian aggression of the sovereign nation of Ukraine provides a stark warning of the undiminished possibility of nuclear war.

In Memoriam

My college professors showed a grainy clandestine movie of the effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. One of my college roommates had been stationed in Sasebo, and his visit to Hiroshima had inspired him to seek a conscientious objector discharge from the Navy. I read John Hersey’s account of the same. I was there, on June 12, 1982, in New York City, with at least 800,000 of my closest friends, to advocate for a Nuclear Freeze.

Later, as a young graduate student, I would moderate a panel of visiting hibakusha, survivors of the atomic bombings of Japan, at an academic peace conference. When I said to the eldest member of the delegation that I no ability to apologize for my nation, but I was sorry nonetheless, he apologized for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

As the debate over nuclear war continued in Beltway and in the streets, “The Day After,” and the somewhat more grim UK offering “Threads,” tried to project the aftermath of a nuclear exchange, just as “Extrapolations” would do for climate change decades later. The sociologist David Meyer, who blogs at “Politics Outdoors,” would write a well–researched book about the Nuclear Freeze Movement, A Winter of Discontent.

I was disappointed to hear on NPR that an entire Smithsonian exhibit about the atomic bombings was scrapped due to protests that one part of an exhibit, which featured a debate of the morality of the atomic bombings, was somehow “disrespectful to veterans.” [“Trump's impeachments have been removed from a Smithsonian exhibit, for now”] I’ve met a veteran who flew one of the bombing runs. He was forever morally scarred by his participation.

Today, public television has made available several retrospectives: “The Bomb,” a retrospective on the development of the atomic bomb; “Atomic People,” about the surviving hibakusha; and “The Atomic Bowl,” a feature film about a football game played at Ground Zero in Nagasaki, five months after the bombing.

Few will forget the blockbuster Oppenheimer.

But how many know of “Grave of the Fireflies,” a feature–length anime about two orphans trying to survive in 1945 Kobe, Japan.

What I find most heartbreaking about this offering from the famed Studio Ghibli, which also gave us “Spirited Away,” and other work by Miyazaki, is the portrait of societal collapse that characterized Japan in 1945. The orphans’ own relatives had, in a family–centric culture, turned them away for lack of food. This portrait adds a human dimension to historical accounts of the US decision to use nuclear weapons on Japan. The US pursued unconditional surrender, despite backchannel negotiations to end the war. Some suggest racism was a factor in the decision, relative to the end of hostilities in the European theatre of the Second World War.

Many organizations have tried to the threat of nuclear war in the public eye, despite its tendency to wander elsewhere. One the decades, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has updated its “Doomsday Clock,” moving it one second closer to midnight this year.

Adding to the danger of intentional or accidental nuclear war, we also learn today that “AI soon could be baked into the system” of the decision to use nuclear weapons.

All of this danger aside, the argument for abolition always also was that the money used to research, develop, test, and deploy nuclear weapons would be better directed to that satisfaction of human needs. Indeed, analysis of armed conflict zones demonstrates a correlation with a lower UN Human Development Index. It’s a truism that arms races cause the poor to starve.

In this, the ninth decade of the nuclear era, we must redouble our efforts to steer the world away from the threat of nuclear annihilation and toward the devotion of resources to meet human needs.

Like this post? Please share.

Care to join in discussion? Please comment.